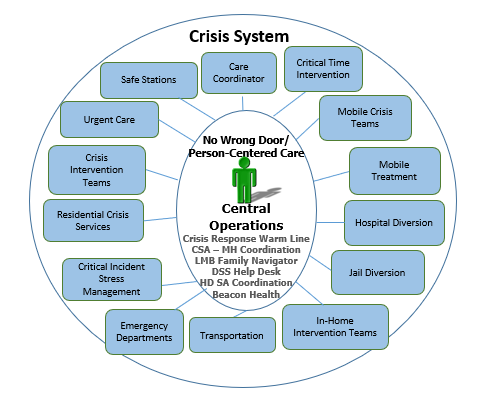

Of the many programs provided through the Anne Arundel County Mental Health Agency (AACMHA), the Crisis Response System (CRS) stands out as one of the most innovative crisis systems throughout the state.

Individuals with mental health and substance use disorders who are experiencing a crisis have traditionally been treated in hospital emergency departments or have become incarcerated. Both options are not only costly, but their staff often cannot provide the specialized treatment and aftercare needed by someone with a behavioral health issue.

In response to the growing need for crisis services and the desire to serve individuals in the least restrictive setting, AACMHA developed the CRS to provide an array of behavioral health options and supports for individuals in distress.

In September 2024, the AACMHA Crisis Response was awarded CARF Accreditation. This is a significant achievement and reflects the dedication and commitment from our Agency to improving the quality of life for those we serve in our community.

Care Coordination is the most effective component of Anne Arundel County’s CRS, an element that also makes it stand out from other systems.

This is the follow-up that is conducted with individuals after their immediate crisis is resolved. Warm-line operators conduct follow-up calls to individuals who call for services and resources. The operators also contact providers to coordinate care. In addition, there is a care coordination element of CRS that can offer more than a follow up call if the situation requires intense support.

Follow-up is also conducted for individuals seen by the Mobile Crisis Teams (MCT). These short-term crisis stabilization visits are an important aspect to ensuring that individuals are able to remain stable and mitigate additional crises.

Information on Critical Time Intervention (CTI) from the Center for the Advancement of Critical Time Intervention:

“The CTI model was developed in New York City during the mid-1980s when many people with psychiatric disorders were becoming homeless. In response to the homelessness crisis, a number of clinicians, researchers and other advocates began meeting to discuss how to alter services and housing to accommodate people who were homeless and mentally ill. Many “good practices” of community mental health care, which we take for granted today and were not in wide use at the time, evolved during those years of collaboration and innovation.

It was in this context that the idea for CTI was conceived. While working on an onsite mental health team in a large municipal men’s shelter in the South Bronx, the developers of CTI (Ezra Susser, Elie Valencia, Sarah Conover) observed that many of the men who had been placed into housing became homeless again. Discharge planning helped the men up until placement in housing, but it did not provide the type of assistance they needed to remain in housing. Transitional periods like the move from shelter to permanent community housing, when clients have to navigate a complex and fragmented system of care, are especially challenging.

CTI was designed as a short-term intervention for people adjusting to a “critical time” of transition in their lives. The developers hypothesized that the men in the shelter would meet with more sustainable success if they were connected to long-term support from community resources. Thus, if the CTI team maintained continuity of care during the first nine months of the transition while simultaneously passing responsibility on to community supports, then this support would remain in place after the end of the intervention and would enable the effects of a time-limited intervention to last long after its actual endpoint. From the beginning, CTI was thought of as an intervention that could be applied to other contexts.”

The Mobile Crisis Teams (MCTs) were designed to respond primarily to calls from police officers and are on police radios. In addition, if the OPS receives a call regarding an individual who is in severe crisis, they have the ability to refer calls to one of the county’s MCTs.

The MCT can then be dispatched to assist in stabilizing the individual and connect them to the most appropriate services. During FY22, the MCTs were dispatched 3,126 times. The agency serves the entire county on a 24/7/365 basis.

On days when there are sudden surges, AACMHA employs contingent part time staff (CPT) to assist.

People Encouraging People provides Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) in Anne Arundel County.

Information on Assertive Community Treatment from the Center for Evidence-Based Practices:

“Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) is an evidence-based practice that improves outcomes for people with severe mental illness who are most at-risk of psychiatric crisis and hospitalization and involvement in the criminal justice system. ACT is one of the oldest and most widely researched evidence-based practices in behavioral healthcare for people with severe mental illness.

ACT is a multidisciplinary team approach with assertive outreach in the community. The consistent, caring, person-centered relationships have a positive effect upon outcomes and quality of life. Research shows that ACT reduces hospitalization, increases housing stability, and improves quality of life for people with the most severe symptoms of mental illness.”

Under the Hospital Diversion Program, a clinician is co-located at Luminis Health Anne Arundel Medical Center (AAMC) and the University of Maryland Baltimore Washington Medical Center (BWMC) to follow-up on any individuals entering an Emergency Department under emergency petitions the previous day.

This clinician consults with hospital staff to determine if there is an alternative to an inpatient stay for the individual. When it is determined that the individual could be safely discharged, the clinician works with the individual to connect them to community services.

Should the individual need more intensive services, placement in a crisis bed is an option. A crisis bed allows the individual to be discharged from a more restrictive hospital inpatient unit while receiving crisis stabilization services. Individuals are able to remain in the crisis bed for up to 10 days. Should additional days be needed to stabilize the person in crisis, the clinician works with the provider to obtain authorization from the State’s ASO.

A Jail Diversion program was established in January 2015 to augment the AACMHA Crisis Response System. The program was initiated at the Jennifer Road Detention Center where pre-trial individuals are detained.

The focus of this program is individuals who are: in pre-trial status, charged with a misdemeanor, and have screened positive for a behavioral health disorder. Individuals who participate in the program must be willing to receive community-based services upon release.

Once the individual is referred to the program, the Jail Diversion Specialist screens them. If the individual is accepted in the program, a plan of care is developed and submitted to the judge for review at the 1:00 p.m. docket.

If the attorney and the judge approve the plan, the individual is released the same day and the plan of care is implemented. This plan includes strategies to address housing needs, mental health and substance use disorder treatment, physical health, and attainment of benefits.

The individuals can receive services for up to 90 days post-release and they are then transitioned into services in the Public Behavioral Health System (PBHS) or other programs if they are privately insured.

The In-Home Intervention Program for Children (IHIP-C) is a family-focused, community based, in-home intervention program utilized in Anne Arundel, Calvert, Charles, Prince George’s, and St. Mary’s Counties.

It provides services for children and adolescents with behavioral health issues, who are at risk of out-of-home placement. IHIP-C utilizes a strengths-based, family-centered approach providing individualized, coordinated treatment and skill building to the child and their family.

As part of an integrated approach, the team often engages not only the child and family but other key participants that may influence the child’s overall well-being, including school staff, probation officers, psychiatrists, or extended family.

This program allows youth to remain in their homes thereby significantly reducing the need for institutional care or out of home placement.

There are two emergency departments in Anne Arundel County.

Luminis Health Anne Arundel Medical Center (Annapolis)

University of Maryland Baltimore Washington Medical Center (Glen Burnie)

In addition, the Arundel Lodge Behavioral Health Urgent Care Center on the campus of Luminus Health Anne Arundel Medical Center is open Monday-Friday, 9:00 AM-9:00 PM ET.

Most Crisis Response Staff receive Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) training.

Information on Critical Incident Stress Management from Critical Incident Stress Management International.

“Critical Incident Stress Management or CISM, is an intervention protocol developed specifically for dealing with traumatic events. It is a formal, highly structured and professionally recognized process for helping those involved in a critical incident to share their experiences, vent emotions, learn about stress reactions and symptoms and given referral for further help if required. It is not psychotherapy. It is a confidential, voluntary and educative process, sometimes called 'psychological first aid'.

First developed for use with military combat veterans and then civilian first responders (police, fire, ambulance, emergency workers and disaster rescuers), it has now been adapted and used virtually everywhere there is a need to address traumatic impact in people’s lives.

There are several types of CISM interventions that can be used, depending on the situation. Variations of these interventions can be used for groups, individuals, families and in the workplace.”

Two providers are licensed for Residential Crisis Services in Anne Arundel County.

A vital component of the Crisis Response System (CRS) has been the partnership with the Anne Arundel County Police to implement Crisis Intervention Teams (CITs).

The CITs consist of an officer trained in CIT and an independently licensed, behavioral health clinician. The advantage of having a CIT is that they are able to respond in situations where Mobile Crisis Teams (MCTs) are not, such as when weapons or barricades are involved, or as first arrival at schools until a parent/guardian can be reached.

These teams also provide a comfort to county residents, as a police officer can go onto someone’s property to perform a “well-being” check, where no other component of CRS is able to do this.

On April 20, 2017, a new pilot program, “Safe Stations”, was implemented in response to the growing opioid epidemic and the Governor’s declared State of Emergency.

Safe Stations allows persons with substance use disorders (SUDs) who are looking for treatment to walk into a police or fire station and request assistance.

Once at the station, the individual will be given a medical assessment by emergency medical services (EMS) personnel.

If they do not need immediate medical attention, a Crisis Response team is contacted to provide further access to SUD treatment and follow-up care.

If the individual does require immediate medical attention, they are transported to the emergency department (ED) by EMS and a Mobile Crisis Team (MCT) will meet the individual in the ED.